French and Indian War |

|---|

Background

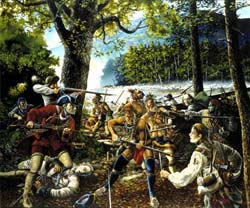

After the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle finished that earlier war, the hatred between the French and the English in the Americas never quite waned. It must be understood, that in 1755 France held most of America. The French land claims covered Canada (close to what we know know as Canada), as well as New France (that is, the stretch of land following the Mississippi River all the way to Louisiana). The English, wanting to expand their land, often moved into the land claimed by the French. This encroachment forced the French to build several forts along the frontier. Some of these forts were Fort Duquesne (Near present day Pittsburgh), and Fort Miamis. The French, never lovers of the English due to hundreds of years of fighting, sent the Indians who allied themselves with the French in raiding parties in retaliation for raids conducted by the Indians on the English side, who claimed that their raids were in retaliation for those made by the French. It didn't matter which side was correct, the main object wasn't to retaliate, but rather for the French to keep the English in their place, and for the English to irritate the French as much as possible until they moved out. Tensions BuildWith the tensions already riding high, the French began to build little Fort Le Boeuf downriver from Fort Duquesne, near Lake Erie. The English at this time claimed this land as their own. After some debate, the English decided to send a certain Major George Washington to the region of Fort Duquesne and evict the French. Washington, then 22 years old, headed a small party through the woods. While advancing, he came upon a party of French who were probably scouts. Washington gave the order to fire, and in the battle that ensued 10 French were killed, and some 22 captured. This, of course, was at a time of official peace. Washington was accused by the French of coldly leading an assassination of those men who were killed, and in fact even tricked Washington into signing a document that was translated into saying that he had attacked the party. In fact, the document he signed stated that he had Assassinated, rather than Attacked the party. The world suddenly took note. England, in early 1755 sent two of their regiments to the colonies "to protect the colonies from the Indian invasions". The King of France, still hoping that the peace could be retained, nevertheless sent several regiments of his own to New France: "To defend their frontiers". With this detachment was the Baron de Dieskau, commander, who was under direct orders to only defend the country, and not to instigate an attack. Battles BeginHowever, while this was going on, the English sent General Braddock with a larger force than Washington had to attack Duquesne. The English army marched in their columns towards Duquesne in the typical European manner. In long rows of men, three abreast, they marched down the road to battle. They didn't see the Canadians and Indians hiding in the surrounding woods until it was too late. For the French side it was as good as target practice. For the English it was a massacre. Each time the English soldiers tried to break ranks and join in the same brand of warfare that the French side was using, the English officers beat their men back into their columns. THIS is how battles were fought, the feeling was. (Surprisingly, the English, and later the United States armies followed this method of fighting through even the Civil War. Remember the pictures of men, all lined up across a field even though there were those ominous, and all-too-accurate cannon facing them?). The English were naturally butchered, and were forced to retreat. The French troops coming to America had problems of their own. While at the Great Banks, the fleet became entangled in a heavy fog and became separated. While most of the ships made it to Louisbourg safely, three ships were delayed: The Lys, the Alcide, and the Actif. The Alice, coming to a clearing in the Fog, found itself face to face with 11 English ships. A worrisome moment, but they were at peace, weren't they? (Of course one was never sure. In those days, word was passed by ship, and sometimes one would not know the most current news for months). The flag ship of the English fleet came broadside to the French vessel. Commander Hocquart of the Alcide called out to the English Commander Howe, of the Dunkirk, "Are we at Peace, or War?" Howe replied "Peace", and a short conversation began when the guns of the Dunkirk spit fire through the side of the Alcide. Almost all hands on that ship were lost. The Lys, seeing that the English meant no good, attempted to flee but was eventually captured. Only the Actif was able to disappear into the fog and escape. Clearly the peace was little more than a figment of one's imagination. Angered by this attack, the French King withdrew his entire staff of negotiators from English soil. It wasn't officially war yet, but something was definitely in the making... By August 1755 The situation had settled to a certain degree into a typical war-like state. Except that there was still no official declaration of war made as of yet. Dieskau, commanding the French forces in America, had taken the advise of Governour Vaudreuil and decided that the English forts at Oswego were a menace and needed to be removed. The Regiments of Guyenne and Bearn had already been sent to Fort Niagara, and now Dieskau had two Regiments of La Reine and Languedoc marching west towards Oswego. But before these regiments reached La Presentation (present Ogdensburg, NY) the French had finally translated the documents that were captured on the field of battle during Braddock's defeat at Duquesne. These papers gave the entire English military plans for the rest of the year, and part of that plan was a concerted march of forces up the Lake George/Lake Champlain corridor. Dieskau recalled the regiments of La Reine and Languedoc and re-routed them south to Fort St. Frederic which stood at Crown Point on Lake Champlain. After receiving information that the English had assembled a force at Fort Lydius (later Fort Edward, NY), Dieskau decided to make a defense of an offense. He gathered 200 men from the two regiments he had at his disposal. (most books claim that he took only the Grenadier regiment of each company, but this is not entirely true, as the actual Grenadier companies from each of the regiments were captured aboard the Lys, and so Dieskau had only temporarily created a Grenadier company in each regiment from the remaining men for this most recent purpose. The number of men in a company at that time ranged close to a total of 35 soldiers (in a full complement), and since Dieskau curiously left most of the officers behind, there must have been nearly 130 men taken from companies other than his new Grenadiers) He also brought with him approximately 600 Indians and 600 Canadians. This force traveled south via Bateaux, and then marched to the steps of Fort Lydius. However, after reaching Fort Lydius, Dieskau was forced to change his plans of attack because the Iroquois he had with him refused to attack the fort. Instead, he agreed to march on to the south shore of Lake Saint Sacrament (Lake George) and attack the force of men under the Sir William Johnson. The French force marched some leagues when it became apparent that an English detachment was marching towards them on the road. Dieskau immediately set forth a plan. He sent the Canadians and Indians to hide in the woods on each side of the road while he and the French regiments would stand in their ranks on the road. When the English marched before them and began the engagement, the Indians and Canadians would begin firing, and the entrapped English would be defeated. Whether Dieskau had learned this tactic from the reports of the Duquesne affair, or he had some council from an Indian or Canadian we do not know. It was, however a remarkable plan based on the rigid adherence of most French and English commanders to military habit even in the unfamiliar, and obviously different American frontiers. The plan almost worked. Before the English were totally encircled, however, the story goes, an Indian recognized other Iroquois with the English party and let out a warning. It was considered sacrilege for Iroquois to kill Iroquois, so this story is believable. But the warning did not entirely save the English. As soon as the warning went out, and the French realized what was happening, the firing commenced. According to Dieskau, the English line "went down like a stack of cards". For some time it seemed to be Braddock all over again. The English, realizing that they were being decimated began a fairly disorderly retreat. The French made chase all the way to the English camp at the base of the lake. Here the English put up their defenses. Behind a hastily constructed wall of wood, carts, and other rudiments the English began to return fire with their guns, and cannon. Seeing that the English were well entrenched, the Indians and Canadians faded into the woods and almost out of the fighting. But Dieskau did not retreat. The French forces continued fighting with the sporadic help of the Canadians (who, more used to the Indian style of fighting, must have considered attacking an enemy in the open pure suicide). But now it was the English turn for victory. Dieskau was shot, and his troops began to fall into disarray. The Baron de Dieskau, hours after his first victory in Canada was captured by the English, and now leaderless, and failing miserably, the French were forced to retreat. They returned to Fort Frontenac tired, haggard, and not having eaten for several days. This was the last battle for either side in that theatre for 1755.However, the English still had one huge victory that year, and that was in Acadia. As 1756 dawned, preparations were being made for battles throughout the American frontier. The English were planning an enormous move up the Lake George/Lake Champlain corridor. The French, with the loss of the Baron de Dieskau, was without a commander of forces in New France - but that was soon to change. War still not yet declaredAnd still the official declaration of war had yet to be announced. The first major move of the year was conducted by the French. Although it had yet to play an important part in the war, the three forts at Oswego continued to be a thorn in the side of the French. If manned properly, these forts would be a serious threat to the traffic of men and boats heading west, and the threat to forts Duquesne and Niagara were more than a passing fancy. The Governour of Canada, Vaudreuil had long recognized this threat. When Dieskau was forced to abandon his attack on Oswego and recalled his troops for the defense of Fort St. Frederic, and the Lake Champlain area, the Governour did not lay aside these plans, but only waited for the proper moment to set them in motion. This time came in March of 1756. The first portion of the attack was not, in fact, directed at the forts at Oswego at all. Rather, Vaudreuil focused on the two small forts in Central New York called Fort Bull and Fort Williams. These forts stood along Wood creek in what is known as the Oneida Carry. A Carry was a place where portage was made between disconnected rivers. Often a small "fort" would be built in these places to 1) Protect the carry, and 2) to store goods for future travellers to carry onward. The Oneida Carry stood between the Mohawk river (from which travelers would come from Albany and other points east) and Wood Creek (Which lead into Oneida Lake, and thence onto the Oswego River and to Oswego). To attack these places, Vaudreuil intended to delay the addition of men and supplies to Oswego, and thus make the attack on Oswego easier. To lead this force Vaudreuil chose one of his Canadian Lieutenants: the Chaussegros de Lery. de Lery gathered about him a total of 362 men, including 103 Indians, 8 officers from Louisbourg, and 251 soldiers taken from the Canadian ranks as well as the French regiments of La Reine, Guyenne, and Bearn. The Regiment of Languedoc was not included as they had been at winter quarters at Chambly, and the river was still unpassable. After a long march with many delays, de Lery's force reached Fort Bull on 27 March 1756. After a short battle, de Lery was able to defeat the English. Entering the fort, his men gathered together all the armaments and tossed them into the swampy river where they were sure never to be found, or used against the French again. The fort was then burned to the ground. de Lery then began to march towards Fort Williams, but with the amount of prisoners he had, and when the Indians abandoned him, he was forced to return to Canada. According to de Lery's records, the English losses were 105, and his own being 1 soldier and 2 Indians killed. A small monument now stands near the former spot where Fort Bull once stood (in current Rome, NY), although the area is continuously being built over by shopping strips and new housing. It is my prediction that it will not be long before the site of Fort bull is completely lost much as Fort Edward (at current Fort Edward, NY) is. In a recent trip to Fort Edward it pained me to see that the town has grown over the former fort itself, with the few remaining signs being only a mound or two from the entrenchments and moat running through the backyards of several houses. Current work is going on at Rogers Island (across the river from Fort Edward) to save some of the remains (already picked over fairly well by "amateur archeologists"). War over in AmericaThe war between England and France, though at an end on the continent of America, was still continued among the West India islands, France in this case also being the loser. Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, St. Vincent's,--every island, in fact, which France possessed among the Caribbees,--passed into the hands of the English. Besides which, being at the same time at war with Spain, England took possession of Havana, the key to the whole trade of the Gulf of Mexico. Treaty SignedIn November, 1763, a treaty of peace was signed at Paris, which led to further changes, all being favorable to Britain; whilst Martinique, Guadeloupe, and St. Lucia were restored to France, England took possession of St. Vincent's, Dominica, and Tobago islands, which had hitherto been considered neutral. By the same treaty all the vast territory east of the Mississippi, from its source to the Gulf of Mexico, with the exception of the island of New Orleans, was yielded up to the British; and Spain, in return for Havana, ceded her possession of Florida. Thus, was vested in the British crown, as far as the consent of rival European claimants could give it, the sovereignty of the whole eastern half of North America, from the Gulf of Mexico to Hudson's Bay and the Polar Ocean. By the same treaty the navigation of the Mississippi was free to both nations. France at the same time gave to Spain, as a compensation for her losses in the war, all Louisiana west of theMississippi, which contained at that time about ten thousand inhabitants, to whom this transfer was very unsatisfactory. The conquest of Canada and the subjection of the Eastern Indians giving security to the colonists of Maine, that province began to expand and flourish. The counties of Cumberland and Lincoln were added to the former single county of York, and settlers began to occupy the lower Kennebec and to extend themselves along the coast towards the Penobscot. Nor was this northern expansion confined alone to Maine; settlers began to occupy both sides of the upper Connecticut, and to advance into new regions beyond the Green Mountains towards Lake Champlain, a beautiful and fertile country which had first become known to the colonists in the late war. Homes were growing up in Vermont. In the same manner population extended westward beyond the Alleghenies as soon as the Indian disturbances were allayed in that direction. The go-ahead principle was ever active in British America. The population of Georgia was beginning to increase greatly, and in 1763 the first newspaper of that colony was published, called the "Georgia Gazette." A vital principle was operating also in the new province of East Florida, now that she ranked among the British possessions. In ten years more was done for the colony than had been done through the whole period of the Spanish occupation. A colony of Greeks settled about this time on the inlet still known as New Smyrna; and a body of settlers from the banks of the Roanoke planted themselves in West Florida, near Baton Rouge. Nor was this increase confined to the newer provinces: the older ones progressed in the same degree. This is sometimes referred to as the golden age of Virginia, Maryland, and South Carolina, which were increasing in population and productions at a rate unknown before or since. In the North, leisure was found for the cultivation of literature, art, and social refinement. The six colonial colleges were crowded with students; a medical college was established in Pennsylvania, the first in the colonies; and West and Copley, both born in the same year,--the one in New York, the other in Boston,--proved that genius was native to the New World, though the Old afforded richer patronage. Besides all this, the late wars and the growing difficulties with the mother-country had called forth and trained able commanders for the field, and sagacious intellects for the control of the great events which were at hand. A vast amount of debt, as is always the case with war, was the result of the late contests in America. With peace, the costs of the struggle began to be reckoned. The colonies had lost, by disease or the sword, above thirty thousand men; and their debt amounted to about four million pounds, Massachusetts alone having been reimbursed by Parliament. The popular power had, however, grown in various ways; the colonial Assemblies had resisted the claims of the royal and proprietary governors to the management and irresponsible expenditure of the large sums which were raised for the war, and thus the executive influence became transferred in considerable degree from the governors to the colonial Assemblies. Another and still more dangerous result was the martial spirit which had sprung up, and the discovery of the powerful means which the colonists held in their hands for settling any disputed points of authority and right with the mother-country. The colonies had of late been a military college to her citizens, in which, though they had performed the hardest service and had been extremely offended and annoyed by the superiority assumed by the British officers and their own subordination, yet they had been well trained, and had learned their own power and resources. The conquest of New France, in great measure, cost England her colonies. |

Historians will usually note that the French and Indian War was actually a small portion of what is known as the Seven Years War. This is not entirely correct. While the Seven Years War, and the French and Indian War were related, in fact the French and Indian War being the beginning of the Seven Years War, the conflict in America was more closely tied to the unsettled feelings left over from King George's War (1744-1748).

Historians will usually note that the French and Indian War was actually a small portion of what is known as the Seven Years War. This is not entirely correct. While the Seven Years War, and the French and Indian War were related, in fact the French and Indian War being the beginning of the Seven Years War, the conflict in America was more closely tied to the unsettled feelings left over from King George's War (1744-1748).